IGNITING THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

As immunotherapy becomes recognized as a first line treatment for cancer, others outside of oncology are also researching how to strengthen the immune system both for cancer treatment and for cancer prevention. This line of thought corresponds with the relatively new field of epigenetics, a subset of genomics that studies how genes can be turned on or off — made to express or prevented from expressing. But it also corresponds with the relatively mature field of vaccine production, which has succeeded in wiping out what we used to call the childhood infectious diseases. Vaccines so successfully wiped out smallpox that in 2014 there wasn’t a single case anywhere in the world, and now we no longer routinely vaccinate children for the disease.

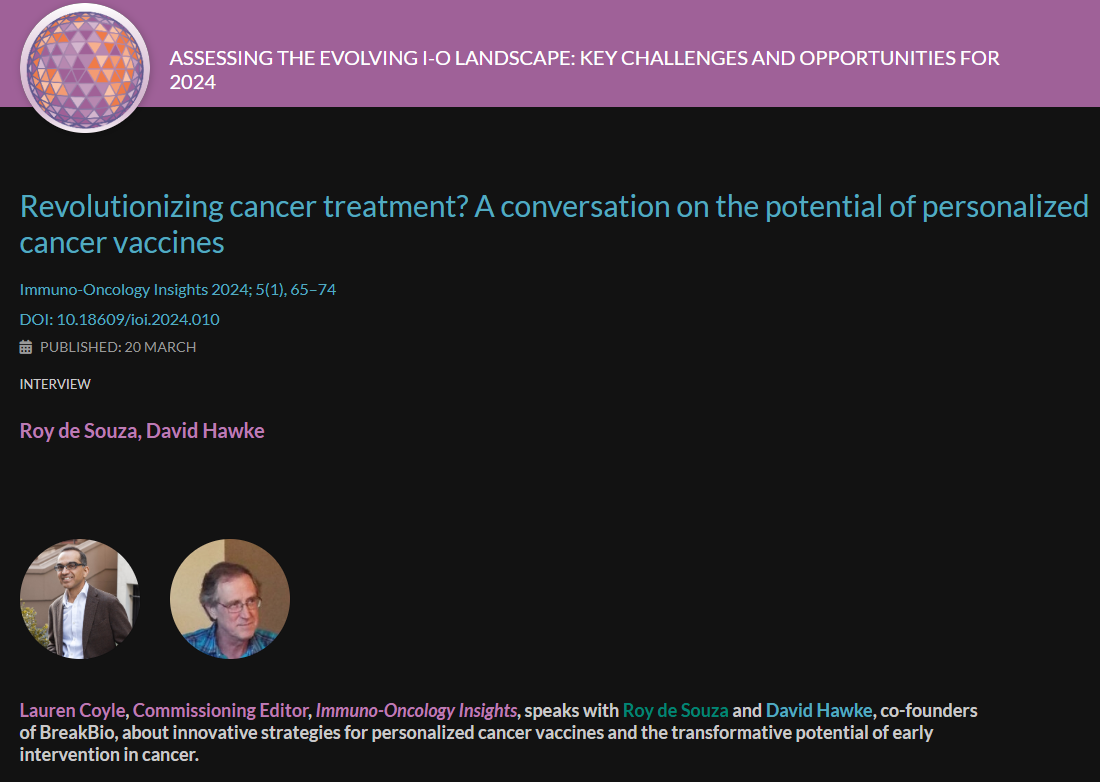

The first success with a vaccine for cancer prevention was the HPV vaccine, which can prevent cervical cancer, and to a lesser extent cancers of the mouth, throat and anus. That vaccine was approved for the US market in 2006, but because of the way it was marketed — as a way to prevent sexually transmitted diseases — it didn’t get the kind of attention it deserved from the lay community.

It did, however, result in its inventors receiving a prestigious Lasker Award (the medical Nobel Prize). Those researchers are now on to another immunotherapy project in which the same virus particles they worked with for the HPV vaccine can infect tumor cells and bind to them. Research is being conducted on this to treat melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer.

Immunotherapy has come so far that the March 2018 issue of Science Magazine was totally devoted to it.

Cancer immunotherapy—the science of mobilizing the immune system to kill cancer—has been pursued for more than a century. Yet only recently has this powerful strategy finally taken center stage in mainstream oncology. The past few years have seen unprecedented clinical responses, rapid drug development, and first-in-kind approvals from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Reports of terminal cancer patients defying the odds and achieving complete remissions are accumulating. These success stories are the culmination of decades of painstaking research by pioneering scientists and physicians. Newly approved immunotherapies include drugs that can manipulate components of the immune system and methods to genetically engineer patients’ own T lymphocytes to recognize and attack their tumors.

But there’s a lot we still don’t know. It’s as if we can see the shadowy outlines of personalized cancer therapies in the future, but not clearly enough to know where and with whom it will work.

This is a problem in the field, because eager cancer patients, unless we are very careful, will be disappointed by treatments that may either be unsafe or ineffective.

But the simple fact is that we still don’t know who will respond to treatment.

In the meantime, there’s another unknown in the equation, and that’s the role of the gut biome. Research into the biome has led us to the obvious but unsung role of food as medicine. Since this deserves its own post, I’ll just leave it there for now, but suffice it to say that diet has been proven to have a role in epigenetics — whether a gene expresses or not.